On the utility of user stories

Published on Oct 16, 2021

User stories are a staple of most agile methodologies. You’d be hard-pressed to find an experienced software developer that’s not come across them at some point in their career. In case you haven’t, they look something like this:

As a frequent customer,

I want to be able to browse my previous orders,

So that I can quickly re-order products.

They provide a persona (in this case “a frequent customer”), a goal (“browse my previous orders”) and a reason (“so that I can quickly re-order products”). This fictitious user story would probably rank among one of the better ones I’ve seen. More typically you end up with something like:

As a user,

I want to be able to login,

So that I can browse while logged in.

This doesn’t really provide a persona or any proper reasoning. It’s just a straight-forward task pretending to be a user story. If this is written in an issue then it provides no extra information over one that simply says “Allow users to login”. In fact, because it’s expressed so awkwardly I’d argue that it’s worse.

This kind of task-disguised-as-a-user-story problem becomes more obvious when people try to write technical tasks in the same way:

As a developer,

I want to refactor the JobFactory,

So that I can work with it more efficiently in the future.

This just says “Refactor the JobFactory”. If you wrote that in a ticket you’d probably feel bad for not describing it very well, but somehow when it’s dressed up as a user story it feels more valuable.

Does the user really want that?

One thing that really irks me about user stories is that it lets you twist your business objectives into sounding like they’re the user’s idea: the story becomes a post-hoc justification for a task you decided was required.

Say you’re making a mobile app for an online book store, and your team for whatever reason has a target of increasing the number of users who view the daily book-of-the-day offer. Maybe you do some interviews and users tell you they forget to check in each day to see what the offer is. How can you funnel more users there?

As a mobile app user,

I want to receive a push notification whenever a new book-of-the-day is available,

So that I have the chance to buy the book.

Some users probably do want such a thing, but I’d argue the vast majority of them do not. Imagine if every app on your phone alerted you whenever there was a new deal, or popped up a dialog whenever you went near a physical shop they had vouchers for…

Obviously in the cold reality of capitalism businesses make money by doing things not strictly in the interests of users[1]. When written up like this it becomes so painfully disingenuous, though. Despite writing a user story that starts with the words “As a user”, you’re not really putting yourself in the user’s shoes.

Who even is the user?

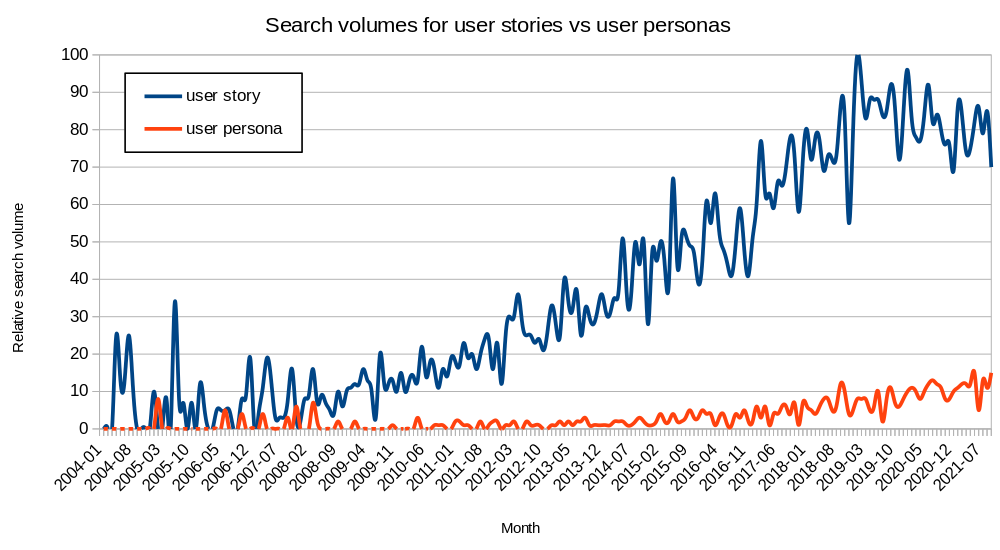

One of the big benefits of user stories comes from using personas to describe users. It’s also one of the things that’s rarely actually done, at least in my experience. Looking at Google Trends you can see the rise of searches for “user story” as agile slowly takes over the world, but the movement in searches about personas is very slight:

A lot of the time stories are just written with “As a user”, or have some adjectives tacked on to the start (“as a mobile user”, “as a logged-in user”). The best I’ve ever seen in the wild was specifying the class of user like in the example at the start: “as a frequent customer”, or “as a visually impaired user”.

The problem with using these classes is it requires you to come up with them when you’re writing the story. Maybe one day you think about visually impaired users, but the next you don’t. Maybe Bob thinks about certain classes of users, but Alice concentrates on different ones.

The ideal way to solve this is to come up with personas that all the team understand. For example:

- Kiera is addicted to books. She reads across genres, and often buys books to gift to her friends and family. She has piles and piles of books to read, but that doesn’t stop her ordering more if she sees a good deal. She likes receiving new books almost as much as reading them, and opts for the fastest delivery available.

- Sharon is a slow, methodical reader. She buys one book at a time when she’s close to finishing her current one, and gifts or resells her old books. She almost exclusively reads Science Fiction, and will generally read complete series from start to finish. She’s short-sighted and often struggles when using mobile phones or computers.

You’d probably want 2-4 personas that collectively represent most facets of your userbase. They can be a lot more fleshed out than these - if you search for example user personas you’ll find many beautifully presented examples that have complete backgrounds including hobbies, education levels, and so on. Even with this minimal level of detail, though, I’d argue they’re more useful than just writing things in a standard user story form.

Thinking back to the story about push notifications, writing it to use one of these two personas forces you to think about the trade-offs involved. Kiera probably would like a notification, but it would annoy and possibly confuse Sharon. This then leads you down the path of considering how to accommodate both types of user — maybe adding it as an option, or doing some fancy machine learning, etc. The conversation is now focused around the users, rather than steamrolling over them to reach a business objective.

You’re holding it wrong

The problems I’ve described are not a problem with user stories per se, but rather common issues with how they’re used. But there’s only so many times you can tell people they’re holding a tool wrong before you have to accept that maybe the tool was badly designed.

Considering features from the perspective of multiple personas is the single best thing you can possibly do to ensure you’re providing value to your users. You don’t even need to write things in the typical user story style to benefit from this.

Tacking “As a user,” to the start of all your JIRA tickets isn’t being agile, and isn’t good for users, even if it lets you tick a box somewhere. In some cases this lip-service to users is actively detrimental to them. We should be valuing users and personas over stilted templates and check-box exercises (remind you of anything?).

-

As a user, I want to pay more money for the things that I buy, so that the company’s CEO can afford to go to space. ↩︎