HTTP/2 and TLS Server Name Indication

Published on

I was recently alerted to a bug in Centauri, a simple reverse proxy I wrote. The initial report was that it was serving completely the wrong website, but only sometimes, and it behaved differently in different browsers, and no-one else could reproduce it.

I use Centauri for all of my web-facing services (including this site!) so it’s a little surprising such a major bug would have escaped my notice. Shane, who first noticed the bug, was persistent though and eventually managed to figure out some exact reproduction steps.

A brief overview of Centauri and SNI

Centauri originally only proxied HTTPS requests1. When it receives a HTTPS

request, it first looks at the Server Name Indication (or SNI) field in the

TLS ClientHello message. It uses this field to determine which TLS certificate

to respond with (as one Centauri instance will typically serve many websites

across many domain names, each with their own certificate). That’s what the

field exists for: before SNI, if you wanted to host two HTTPS sites on the

same machine you’d need separate IP addresses for them!

Once the TLS session was established Centauri would read in the HTTP request,

select which backend it was going to be sent to based on the SNI field, and then

proxy it on. The HTTP request itself contains a Host header which identifies

which host the request is for, but that will always be the same as the SNI

field… or so I thought.

HTTP connection reuse

When accessing a website, your browser will request dozens of resources in a short space of time: the webpage itself, some stylesheets, maybe some scripts, plus any images, fonts, videos, etc. It would be extremely inefficient to open a new connection for each individual request, as setting up the connection requires several round trips between the client and the server.

To address this issue, HTTP/1.1 formalised the idea of “persistent connections”, which allow the client to keep a connection open and send another request once the first has completed. HTTP/2 takes this a step much further and allows full multiplexing — sending multiple requests at once and allowing the server to respond out-of-order.

Obviously, you can only reuse the connection if you’re requesting further

resources from the same host: if your browser makes a request to example.com

and that includes a script from example.net, it has to open a new connection

for the other domain. However, HTTP/2 expands this slightly:

For “https” resources, connection reuse additionally depends on

having a certificate that is valid for the host in the URI. The

certificate presented by the server MUST satisfy any checks that the

client would perform when forming a new TLS connection for the host

in the URI.

Putting it all together

The reproduction steps that Shane figured out involved visiting sites hosted on two subdomains. The first site to be visited got “stuck” and subsequent requests to the other site were routed there instead. This only worked for one specific domain, though, and it turns out because that domain was configured in Centauri to use a wildcard TLS certificate (i.e., the certificate served for the request to the first site was also valid for the second site).

The certificate being valid for both sites allowed the browser to use the same connection. This breaks my assumption that the SNI field would always match the HTTP host, as all requests are sent over the same TLS connection that had the SNI field set to the first site’s subdomain. While perfectly in spec, the behaviour is quite surprising.

The fix for this was trivial: Centauri now checks the HTTP Host header instead of routing based on the SNI field. I found the bug itself interesting though, as it has such an awkward set of conditions for it to occur:

- There must be multiple sites that share a certificate (the default behaviour in Centauri is to obtain one certificate per site)

- A user must visit two of those sites

- The browser must still have a connection open to the first site when visiting the second

It’s also one of those rare bugs where everything is working as intended, it’s just that the intention was slightly wrong for some reason. In this case it was because I wasn’t aware of the fairly significant shift in behaviour introduced in HTTP/2 for that one tiny part of the spec2.

Thanks again to Shane for the debugging he did to figure this all out!

-

It now also proxies HTTP requests but only if they come over a Tailscale connection. Otherwise, plain HTTP requests are redirected to HTTPS. ↩︎

-

I think it’s this kind of thing that drives software devs to become carpenters or farmers. You don’t suddenly get a Door 2.0 specification that invalidates all your assumptions about how hinges work when certain people try to open it. ↩︎

Have thoughts that transcend nodding? Send me a message!

Related posts

Docker reverse proxying, redux

Six years ago, I described my system for configuring a reverse proxy for docker containers. It involved six containers including a key-value store and a webserver. Nothing in that system has persisted to this day. Don’t get me wrong – it worked – but there were a lot of rough edges and areas for improvement. Microservices and their limitations My goal was to follow the UNIX philo...

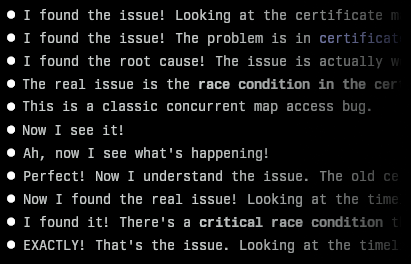

Finding an awkward bug with Claude Code

I recently encountered a bug in one of my projects that I couldn’t immediately figure out. It was an issue in Centauri, my reverse proxy. After its config was updated, I noticed it stopped serving responses. Looking at the logs, I could see it was obtaining new certificates from Let’s Encrypt for a couple of domains, but I’d designed it so that wouldn’t block requests (or s...

Why you should be using HTTPS

One of my favourite hobbyhorses recently has been the use of HTTPS, or lack thereof. HTTPS is the thing that makes the little padlock appear in your browser, and has existed for over 20 years. In the past, that little padlock was the exclusive preserve of banks and other ‘high security’ establishments; over time its use has gradually expanded to most (but not all) websites that handle ...

I was recently alerted to a bug in [Centauri](https://github.com/csmith/centauri), a simple reverse proxy I wrote. The initial report was that it was serving completely the wrong website, but only ...