An introduction to containers

Published on

I’m a huge fan of (software) containers. Most people I know fall in to one of two camps: either they also use, and are fans of, containers, or they haven’t yet really figured them out and view them as some kind of voodoo that they don’t really want or need.

I’m writing this short guide to explain a little how containers work - and how running something in a container isn’t really that much different to running it normally - to hopefully enable more people in that second group to give them a try. It’s aimed at people who have a fairly good grasp of how Linux works.

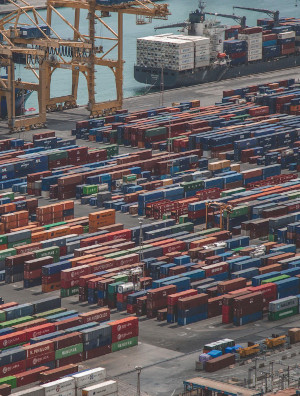

Containers are often mentioned in the same breath as VMs, which is not a helpful comparison or analogy. Think of containers as standard units of software, much like how Intermodal containers are standard units of freight transport across the world. When a company internationally ships goods in volume there isn’t a question about how they’re packaged - they go in an intermodal container. The same container can be deployed on a freight train, a lorry, or a ship. The haulage company doesn’t need to care what’s in the container because they’re completely standardised. Likewise, with software containers you don’t really need to care about what’s inside: the software you’re deploying could be written in Go, Python2, Python3, Bash, PHP, LOLCODE, or anything[1].

What does a running container look like?

When you run a container, you’re just running a process. In a lot of ways it’s not very different to what happens if you were to start the same process on the host computer.

For example I have a container that just runs cat(1). With no arguments, cat will

read from stdin until it receives an EOF, so it’s handy to test with. If I run ps a on my

computer, I can see the cat process in amongst everything else I’m currently running:

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

7199 pts/1 Ss 0:01 /usr/bin/zsh

323806 pts/0 Ss+ 0:00 /bin/cat

324120 pts/4 R+ 0:00 ps a

The /bin/cat process is in a container, and the ps a underneath it is just running

like normal on my desktop. They look very similar, right? If I look under /proc/323806 I can

see all the usual attributes, the same as any other process running.

If I run ps in a container, though, it’s a different story:

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

1 pts/0 Rs+ 0:00 ps a

So inside the container it looks like there’s only one process running. It can’t see anything running “outside” on my desktop. The secret here is that this isn’t a special container trick: this is just a feature of the Linux kernel called namespacing.

If we go back to procfs and look at the ns/pid node we can see the process in the container is

in a separate PID (process ID) namespace to the one on my desktop:

# readlink /proc/323806/ns/pid

pid:[4026534564]

# readlink /proc/7199/ns/pid

pid:[4026531836]

Almost all[2] processes running ‘normally’ on my desktop have the same PID namespace, whereas each container gets their own by default. PID namespaces are hierarchical: a new process is assigned a PID in its own namespace, and the parent namespace, and the grandparent namespace, and so on. That’s why I can see the process running in the container from my normal shell - the container’s namespace is a child of the main namespace all of my desktop software is running in.

Linux supports - and container software makes use of - a bunch of other namespaces too: mount points, network, UTS[3], cgroups, and more. These all play a part in isolating a container from the system it is running on.

You can manually run a process with unshare(1) to “unshare” some namespaces from the parent

process. For example if I run unshare -fp --mount-proc ps a, it looks very similar to running

ps instead the container:

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

1 pts/4 R+ 0:00 ps a

So: a process running inside a container is just a heavily namespaced process running otherwise normally in the operating system. No voodoo magic here!

What about the filesystem? What are ‘images’?

Containers run in their own mount namespace meaning mount points can be different inside the container to

those on the host. This means the container can have a different / mounted to the host,

effectively giving it its own filesystem.

The root filesystem of the container is defined in the container’s image. If I use Docker to run a container

using the Ubuntu image (docker run ubuntu), the root filesystem inside that container will

resemble a minimal ubuntu install. Note that this is just the filesystem: the container doesn’t have its own

kernel.

You might be thinking that sounds pretty inefficient. Downloading Ubuntu is definitely not instant, and doing it for every application you run would be insane! Quite. Containers solve this by using filesystem layers. These are stacked on top of one another to create the final filesystem. Each layer can be retrieved and cached independently of all others.

Say (for simplicity) that the Ubuntu image is a single layer. If I run one container with that image, then the layer will be downloaded and cached once. If I run three hundred containers with that image then the layer will be downloaded and cached once. Even better, if I use another image that’s based on Ubuntu but adds some software on top, only the “on top” layer will be downloaded if I already have the relevant “Ubuntu” layer cached.

If all the layers are cached, what happens when you change a file? This is dealt with using the copy-on-write technique: when you modify a file it is copied from the source layer and the changes are only made in a new layer. This is handled by the OverlayFS filesystem which is part of the mainline kernel.

When a container is running, changes made to its filesystem are temporary, and do not persist across

container restarts. To persist data - or introduce new data to a container - you can mount volumes. How this

works varies depending on how you’re running your container, but at the basic level it is pretty much the

same as bind-mounting (mount -o bind).

You may be familiar with using chroots to change the apparent root directory of processes,

perhaps with full-blown “jails” built on top. Containers offer much better isolation thanks to the use of

namespaces. Instead of being constrained to a portion of the host’s filesystem, they don’t even have it

mounted! Containers also get to specify their environment - if they expect in certain places, for example -

instead of the sysadmin having to manually set up the chroot. Finally, containers offer much more

fine-grained control over what processes can do (if you want it), and allow much more advanced use-cases

such as inter-container networking.

Images and filesystems employ a little magic to ensure that layers are reusable and cacheable, but again there’s nothing terribly special about them: a container has a filesystem that appears to it to work the same way as a filesystem on the host, and it’s using a standard filesystem shipped with the kernel.

How about networking?

Again, networking is namespaced, so a container has its own network stack, its own virtual network interface, its own IP address and so on. How that network interacts with your real network depends on how you’re running the container. Docker, for example, can add iptables rules to NAT traffic between containers’ networks and the outside world.

Containers can generally be connected into networks, and can communicate amongst themselves without the traffic actually leaving the host machine. This allows you to, for example, run a SQL database and connect it to a web application without ever exposing the database to the outside world. Moreover, as well as being isolated from the outside world, it’s isolated from other containers in other networks. If one of your applications has a crazy bug or is compromised, this significantly limits the damage it can do.

You have to explicitly opt in to “publishing” ports from a container, which exposes them to the outside world (either directly, or via a load balancer or some other middle-man, depending on how you’re running the container). This means you can pick and chose how the outside world sees the app you’re deploying: if it’s a web service that listens on both port 443 and port 80, you can chose to only expose the encrypted port.

If you run some containers and create some networks, you can see the interfaces and bridges on the host:

$ ip l

...

6: br-2405a8cc0445: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP mode DEFAULT group default

link/ether 02:42:3e:fa:23:62 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

8: veth8ed0735@if7: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue master br-2405a8cc0445 state UP mode DEFAULT group default

link/ether b2:c1:5d:55:26:9b brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 2

10: veth541d84b@if9: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue master br-9d7bc4024c1a state UP mode DEFAULT group default

link/ether 86:aa:5f:ee:da:1a brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 1

This shows a bridge and two virtual NICs, just the same as if you’d manually created them (albeit with seemingly random names). So: as before, nothing special here.

Docker? Compose? K8s? Floccinaucinihilipilification?

(OK, Floccinaucinihilipilification isn’t actually a container technology, as far as I’m aware.)

Docker is the most popular container engine - that is, the bit of software that

actually runs containers. It’s responsible for setting up all those namespaces we found, downloading and

caching image layers, and actually starting and stopping the processes. Docker runs as a system-wide daemon

- when you run a command like docker run ubuntu it actually just instructs the daemon to do the

work.

There are several alternatives to Docker for running containers; one interesting one is Podman which runs containers without a daemon. Container engines have all standardised around the same image format looked after by the Open Container Initiative, so an image you build in Docker can be used in Podman, or pretty much any other engine.

Docker compose is a tool for defining and running multiple-container applications. I mentioned earlier running a database alongside a webapp - in practice to do this you’re going to have to configure a network for them, configure a mount point for the database to persist its data on, pass credentials in to both the database and the application, and so on. Doing all that by hand is tedious and error prone.

Docker compose lets you write “compose files”, which are simple yaml descriptions of the containers you wish to run, their properties, and details about any volumes or networks you may want. Out of the box, docker-compose will create a default network for each compose file you run so the containers within it can communicate.

Kubernetes is a container orchestrator, designed to automate deployment and

management of large numbers of containers. It works with Docker under the hood, but provides a huge amount

of tooling on top to allow you to deploy applications and manage their dependencies. It runs across multiple

physical (or virtual) machines (while still allowing containers to communicate privately), and can support

massive workloads by scaling out services (running multiple copies of a container on different hosts) and

load balancing. Kubernetes is sometimes shorted to k8s (as in K - 8 elided

letters - s) because computer people don’t like long words.

OK, they make sense now. But why bother?

Hopefully if you’ve read this far you’ve already picked up on some of the potential benefits, but this is my personal list:

Isolation. If I run some software in a container, there is very little it can do to upset me. It’s not going to leave bits of itself all over my filesystem, it can’t steal all of the secrets in my home directory, I can even limit its CPU and memory resources if I want. If I decide to stop running it, I just delete the container and it is completely gone: no trace remains.

Ease of use. If you give me a container image I have a very good idea of how to run it already. I might need to do some minor configuration to expose ports or mount volumes, but there’s no question about how to run it, how to make it automatically start, and there’s no “installation” procedure. If I want to then swap it with an alternative (say, move from MySQL to MariaDB), it’s potentially just a case of changing the name of the image I pull.

Dependencies included. Containers just run. Python 2 software includes Python 2

and just work. Python 3 software includes Python 3 and just work. I don’t have a massive headache trying to

run both at the same time, because they take care of their own messes. Similarly I’m not going to have to

install npm or cargo or composer to pull in dependencies for an

application: that’s going to have been done in the build process.

Reproducibility. As a fallout from having dependencies included and being isolated from everything else, containers give you amazing reproducibility. If it “works on your machine” in a container, it’ll almost certainly work in production because it’s the exact same environment.

Standardisation. At the start of this article I called containers standard units of software. One of my favourite advantages of containers is that you basically get an API to list all the software you’re running. Most container engines let you supply labels attached to containers as well, so you can add your own annotations. I use this to annotate services which expose HTTP endpoints, and I have a tool that automatically generates SSL certificates for them and configures haproxy to route traffic to them. I can’t imagine how I’d do this without containers - I imagine it’d involve a lot of manual work.

Hopefully this has helped demystify containers a little. If you feel like I’ve missed something important out, or I’ve left you more confused than when you started, feel free to drop me a note using the feedback form below.

-

OK, maybe you should care if you’re deploying something written in crazy languages like PHP. ↩︎

-

Some multi-process apps, such as web browsers, are starting to use namespaces to enhance security, as do certain package systems like Flatpak ↩︎

-

“Unix timesharing system”; in practice this means having a separate hostname ↩︎

Thanks for reading!

Related posts

Adventures in IPv6 routing in Docker

One of the biggest flaws in Docker’s design is that it wasn’t created with IPv6 in mind. Out of the box Docker assigns each container a private IPv4 address, and they won’t be able to reach IPv6-only services. While incoming connections might work, the containers won’t know the correct remote IP address which can cause problems for some applications. This situation is obviously suboptimal in the current day and age. It’s a bit like not supporting HTTPS on a website – you might not have any issues because of it immediately, but you’re fighting against the currents of progress and are making life worse for your users.

Understanding Docker volume mounts

One thing that always confuses me with Docker is how exactly mounting volumes behaves. At a basic level it’s fairly straight forward: you declare a volume in a Dockerfile, and then either explicitly mount something there or docker automatically creates an anonymous volume for you. Done. But it turns out there’s quite a few edge cases…

HTTP/2 and TLS Server Name Indication

I was recently alerted to a bug in Centauri, a simple reverse proxy I wrote. The initial report was that it was serving completely the wrong website, but only sometimes, and it behaved differently in different browsers, and no-one else could reproduce it.

Docker reverse proxying, redux

Six years ago, I described my system for configuring a reverse proxy for docker containers. It involved six containers including a key-value store and a webserver. Nothing in that system has persisted to this day. Don’t get me wrong – it worked – but there were a lot of rough edges and areas for improvement.

I’m a huge fan of (software) containers. Most people I know fall in to one of two camps: either they also use, and are fans of, containers, or they haven’t yet really figured them out and view them as some kind of voodoo that they don’t really want or need.