Surge protectors: marketing vs reality

Published on

A while back I went down a deep rabbit hole looking into surge protectors, and what all the different numbers mean, and how that affects things in case of a voltage spike. Then I didn’t really do anything with the information, other than bore a few friends, and look around in despair at all the shockingly bad products out there. Time to fix that!

I’m coming at this from the angle of a computer user in a country with very good electrical regulations. If you’re protecting something else, or live somewhere that doesn’t believe in grounding things, your mileage may vary.

Building a better mental model

I think when most of us think of surge protectors, we think of an extension lead with some magical property that stops surges and protects everything plugged into them. It’s a bit like the shield on the USS Enterprise. If we put the shields up in time, they’ll stop everything thrown at them, until at some point they’re overloaded and stop working. Only then will we have problems. There’s even a little LED that goes out when she cannae take it any more, cap’n.

Of course, if that was actually the case, I wouldn’t be writing a blog post. Surge protectors are more like the crumple zone on a car. If you hit something, the crumple zone will absorb some of the impact, but you can quite easily still get injured. If the impact is big enough then the crumple zone will bleed some energy, but you’re still going to have a very bad time. My point here is that it’s not a perfect shield, can be overcome with a single excessive impact, and doesn’t magically recharge back to full strength.

The numbers, Mason! What do they mean?

To understand what protection these things really offer, we need to look at a couple of numbers. Unfortunately, they’re not the numbers that are displayed in the marketing. Sometimes they’re not even on the spec sheet. Most of the time they’re on the actual device, and if they’re not then it’s safe to just assume things are bad.

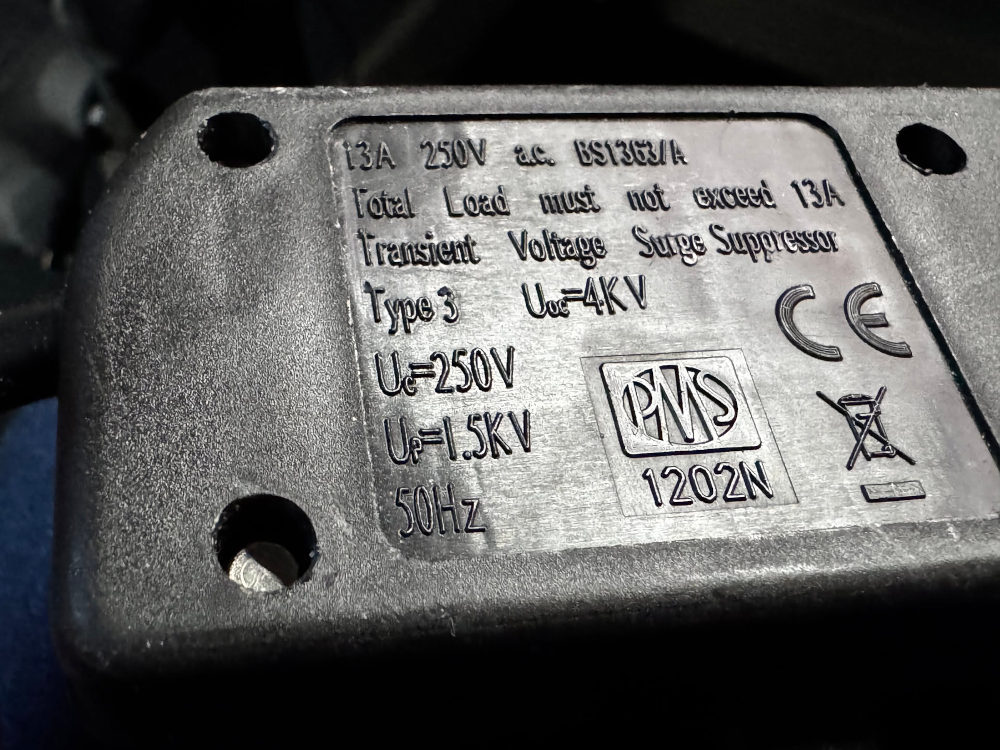

The most important number is the let-through voltage, Up. It may also be called the clamping voltage, the voltage protection rating, or the VPR. This is the voltage that will be let through, before the surge protector does anything1. We use 230V mains, with a +10%/-6% tolerance. So we shouldn’t be seeing anything above 253V. If you were designing a surge protector, you’d want it to engage a little above this, right? Maybe call it 300V so it doesn’t cut in prematurely? If you have a surge protector nearby, I invite you to try and find its Up value. If you don’t have one, you can follow along with mine:

A not-very-good surge protector. Please take a moment to consider how difficult it was to make this text readable.

Yes, that’s 1,500 Volts. Up until that point the surge protector does nothing. Your computer’s power supply just has to deal with it. That’s not even the highest I’ve seen, either. It’s just the closest I had to hand.

So what are the other numbers? Uc is the maximum continuous operating voltage. That’s probably fine — in the worst case it’ll slowly degrade over time if the mains rides the 253V edge — but at the same time, would you not spec it for 275V or more given that? For the most part, we don’t really care about this, though. If the surge protector has the right kind of plug on it, then it’s probably got a Uc in the right ballpark.

Then we have Uoc, which is the open circuit voltage. This is one of the numbers that might end up on the marketing, because it can be big! This is the surge voltage that the device can sustain without failing itself. So for this surge protector, it won’t do anything for surges up to 1.5kV, between 1.5kV and 4kV it will clamp the voltage, and above 4kV it might fail in some manner. That failure could be failing open and leaving your computer to deal with the rest of the surge (the little LED would go out, though!).

The number not on the device that’s on all the marketing materials is the “Joule rating”. That’s how much energy the thing can absorb before it fails. That can be gradually drained by small surges over time, or by a big one. Something in the realm of 1kJ seems to be a “good” value, but what does it actually mean? Say we had a surge of 1.5kV, our 1kJ of protection would cover 0.66 Amp seconds. Surges are typically very short; let’s say one lasts 2µs. That energy budget would allow for 333kA of current to be handled! That’s an order of magnitude more than a lightning strike! Amazing! Except… There’s also a maximum surge current rating, and I guarantee it’s less than that. The actual number on the Joule rating is basically useless given all the other constraints, but the bigger the number the more hardy the protector will be, in general.

Oh, one more thing on that Joule rating. Sometimes surge protectors will have multiple different protection devices inside, especially when they protect other connectors like coax or telephone cables. Sometimes the Joule rating will just be the sum of all the individual protectors, so is even more useless. Yay marketing.

How much abuse can a PSU take, anyway?

OK, so it turns out surge protectors are… underwhelming, shall we say? If there’s a surge, your computer is going to be involved. So what can PSUs actually deal with?

Turns out modern PSUs have surge protection built-in, along with all sorts of other “why is the electricity not electricitying right?” safeguards. I can’t find a single manufacturer that actually puts any numbers to that, though.

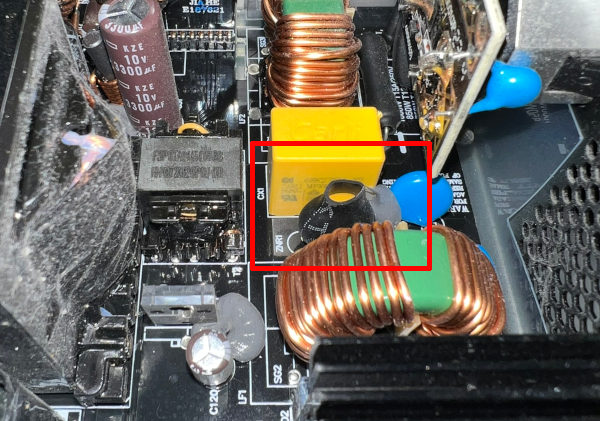

If you were to open one up and look inside, you’d see something like this:

I spy with my little eye… something beginning with MOV!

That little thing hidden in heatshrink is a MOV, or Metal Oxide Varistor. Also known as a Zinc-Oxide Non-liner Resistor, or ZNR, as it’s labelled in the picture. It’s basically a resistor that varies its resistance based on the voltage. So it can have a high resistance at low voltages, and then after, say, 300V it could start dropping off. Can you guess what component is inside basically all consumer surge protectors? Yeah, these things! So, as mentioned, I don’t have numbers to back this up but I’m going to go out on a limb and say that the MOV in a £130 PSU can probably handle at least the same as the MOVs in a £7 surge protector.

It’s hard to imagine a situation where there’s a surge that would have destroyed the PSU that would be mitigated by an external surge protector. It’s probably either going to take both of them out, or they’ll both survive. No Enterprise shields here, I’m afraid.

So is it not worth having a surge protector at all? Not quite. MOVs degrade with use, so if a surge protector handles some smaller surges, or takes bites out of bigger ones, it might prolong the life of the PSU. Maybe that’s worth it, especially if you find one of the (increasingly rare) ones with a decently low clamping voltage.

Addendum: covered equipment warranties and magic smoke

A bunch of surge protectors come with a warranty for downstream equipment. That sounds like a great deal, right? Even if there’s a huge surge that the protector can’t handle, at least you can replace the equipment? Alas, no. These warranties only cover if the surge protector doesn’t operate within its specifications. If you go over the max voltage, or the max current, or the max energy and all your equipment blows up, then the surge protector is merely working as designed. It’s meant to fail in those circumstances, and at that point all bets are off. No warranty money for you.

The other thing to bear in mind is that — in the UK at least — significant power surges aren’t common at all. If you travel with your computer then you’re more likely to come across dodgy electrics that can fry your computer than you are to hit a power surge. I’ve been to a lot of LAN events and have never heard of a surge protector popping and saving a computer; on the other hand I have seen an entire row of computers release their magic smoke because the electrician hadn’t connected the three-phase supply properly. There’s absolutely no protection to be had from that!

Photo credit: thanks to Greg for supplying the picture of the PSU so I didn’t have to take my computer apart.

-

Well, actually, it does a tiny bit before Up because it’s not a binary switch, and life is messy. It won’t do much of anything before Up. ↩︎

Have thoughts that transcend nodding? Send me a message!

Related posts

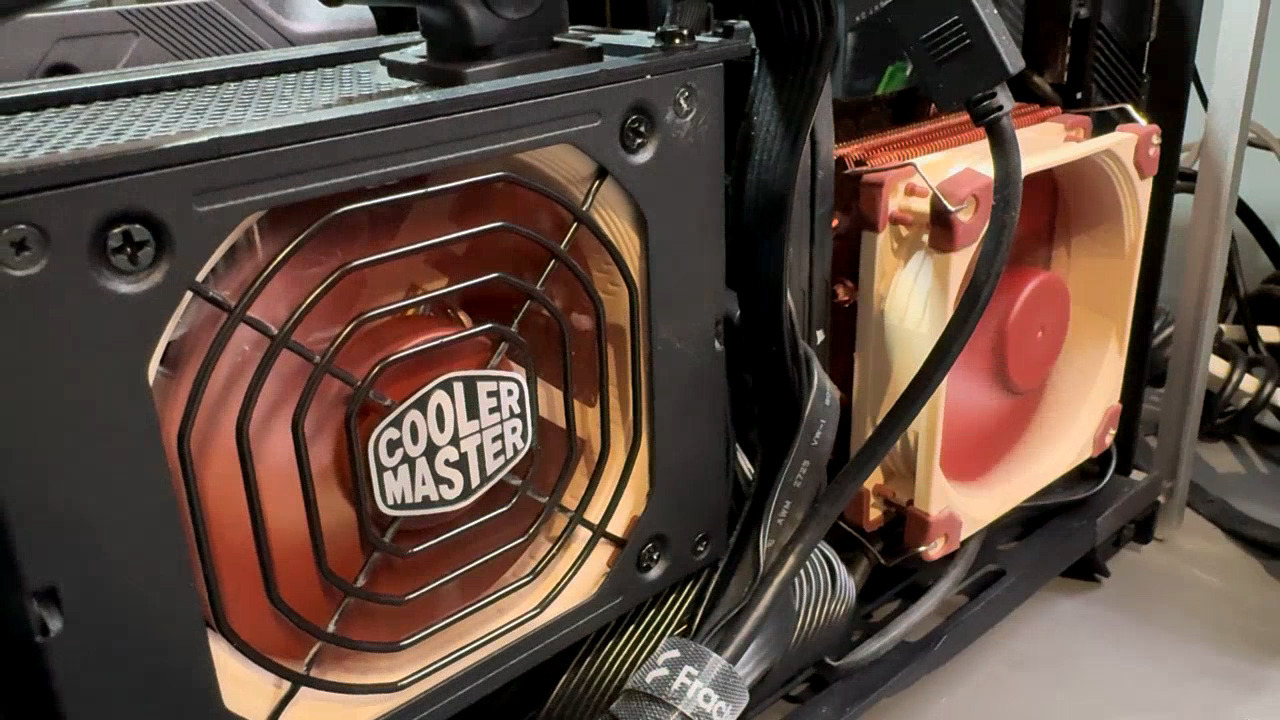

Fixing a loud PSU fan without dying

Three months after I built my new computer, it started annoying me. There would occasionally be a noise that sounded like a fan was catching on a cable, but there weren’t any loose cables to be a problem. Over the course of a few weeks, the sound got progressively worse to the extent that I didn’t want to use the computer without headphones on. I measured the sound at 63 dB, which is a...

Monitoring power draw with WeMo Insight Switches

I recently picked up a couple of Belkin’s WeMo Insight Switches to monitor power usage for my PC and networking equipment. WeMo is Belkin’s home automation brand, and the switches allow you to toggle power on and off with an app, and monitor power usage. The WeMo Android app is pretty dismal. It’s slow, doesn’t look great, and crashed about a dozen times during the setup pr...

Adventures in 3D printing

I’d been idly considering getting a 3D printer for a while, but have only recently taken the plunge. I picked up a Sovol SV06 from Amazon for £199.99, which is a model commonly recommended for beginners. About three weeks later, I think I’ve finally finished fixing all the problems the printer has, and thought I’d document them. Setup and out of the box performance The setup of ...

A while back I went down a deep rabbit hole looking into surge protectors, and what all the different numbers mean, and how that affects things in case of a voltage spike. Then I didn't really do anyt...