Artisanal Docker images

Published on

Artisanal containers…

I run a fair number of services as docker containers. Recently, I’ve been moving away from pre-built images pulled from Docker Hub in favour of those I’ve hand-crafted myself. If you’re thinking “that sounds like a lot of effort”, you’re right. It also comes with a number of advantages, though, and has been a fairly fun journey.

The problems with Docker Hub and its images

Rate limits

For the last few years, I’ve been getting increasingly unhappy with Docker Hub itself. Docker-the-technology is wonderful, but Docker-the-company has been making some rather large missteps. The biggest and most impactful of these has been introducing “pull rate” limits. At the time of writing, if you want to just pull a public image without logging in then you are limited to 100 pulls every 6 hours. If you log in then you’re limited to 200 pulls per 6 hours, but it’s account wide. This might seem like a big enough number, but I repeatedly hit it and there is no way to actually audit what is causing it. I have various containers that may all pull images at arbitrary times (e.g. continuous integration build agents), and the only information you get back from Docker Hub is the number of pulls remaining.

Obviously, I could start paying Docker Hub for a “Pro” plan. That gets you 5,000 pulls per day for $7/month. The downside is that every docker client would have to be authenticated, which presents a fair annoyance in terms of credential management. I also don’t really like how they positioned the service as a public utility with special treatment in the docker software, and then start tightening the ratchet to make money.

“Bad” images

I’m fairly opinionated about what a container image should look like: most importantly it should run just a single process, and only include the bare minimum dependencies required for that. Other people think differently, and it’s very hard to tell at a glance whether an image on Docker Hub contains just the application you want, or whether it also bundles MySQL, Redis, Elasticsearch, and a partridge in a pear tree. Some people want that kind of thing, but I really don’t. It’s also very hard to tell whether an image is officially endorsed by the upstream project, and where the source Dockerfile is. This used to be better because most projects used Docker Hub’s automatic builds, but they’re now a “pro” feature.

I quite often found that I’d be looking for an image for X, and there would be 5-10 images from different users. None of them looked official, some of them were out-of-date, some bundled the kitchen sink. Even when one looked good, it’s a bit of a gamble whether the author is going to keep it updated or not.

Doijanky

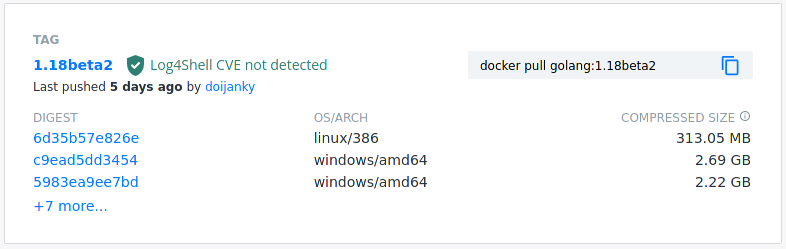

The rate limits and other problems were annoying, but they weren’t really annoying enough to force me to do anything about it. The straw that broke the camel’s back came later: I was looking at the official golang images, and noticed that all the tags were pushed by a random user account called “doijanky”:

An ‘official’ Docker Hub image pushed by user ‘doijanky’

I, perhaps naively, assumed that official images were built on Docker Hub’s own infrastructure. Why would all the Golang images be attributed to this user? Checking out their profile, they’re simply identified as a “Community User” like everyone else, with no repositories of their own. The only thing in the profile is their homepage, which is a link to a Jenkins dashboard: https://doi-janky.infosiftr.net/. It appears legitimate: “Infosiftr” are a container consultancy and the dashboard is linked to from the README in the official images git repository, but I find it baffling that they’re using third-party infrastructure and a normal user account (with a dubious name) to push these images. There doesn’t seem to be a good way to verify what you pull corresponds to the Dockerfile it came from; if infosiftr wanted to inject something into the build they could happily do so, and who knows how good their infosec posture is? If someone got access to the “doijanky” account, how long could they upload malicious images before someone noticed?

This little roller-coaster ride from “are all the official images compromised?!” to “oh, no, they’re not, it’s all just awful” finally convinced me to look at building my own images from scratch.

The implementation: templating with contempt

One of the big issues I needed to tackle was how to deal with updates. I didn’t want to have to go and edit a file every time some minor release was made of some software, or every time there was a security vulnerability in a common library. The official images use a shell-scripting based system to check for updates and generate Dockerfiles, I decided to do something similar but with Go templates. The result is a tool called contempt. It takes a template like:

FROM {{image "golang"}} AS build

ARG TAG="{{github_tag "example/project"}}"

RUN apk add --no-cache \

{{range $key, $value := alpine_packages "git" -}}

{{$key}}={{$value}}\

{{end}}; \

# ...

Contempt has support for getting information from a variety of sources. In this case, it’s getting the latest digest of another Docker image, the latest tag from a Git repository, and the latest version of an alpine package and all its dependencies. The resulting Dockerfile looks something like this:

# Generated from https://github.com/csmith/dockerfiles/blob/master/miniflux/Dockerfile.gotpl

# BOM: {"apk:brotli-libs":"1.0.9-r5","apk:busybox":"1.34.1-r4", <snip> }

FROM reg.c5h.io/golang@sha256:ac8fa5f4078b0a697796b5d741... AS build

ARG TAG="2.0.35"

RUN apk add --no-cache \

brotli-libs=1.0.9-r5\

busybox=1.34.1-r4\

# <snip>

pcre2=10.39-r0\

zlib=1.2.11-r3\

; \

# ...

I’ve cut out the longer parts for readability. You can see that it pins all versions of the alpine packages in use,

as well as the base image. This ensures that if you build from the same Dockerfile at a later time it will build the

same image (or will fail entirely, as Alpine doesn’t keep their old packages around indefinitely). It also produces

a “bill of materials” as a really long JSON-encoded comment. If you let contempt commit the Dockerfile it uses the

BOM to generate useful commit messages like: [project] apk:busybox: 1.34.1-r3->1.34.1-r4, so you can see exactly

what changed.

Contempt also has support for building and pushing images whenever it changes the Dockerfile. I use it in a GitHub action that runs daily to check all my images are up-to-date and push those that aren’t. It understands the dependencies between images (by pre-analysing the templates) so it will always check and build base images before ones that require them. This means an update to, say, the “alpine” base image will cause anything that depends on it to get updated at the same time, ensuring security updates are rolled out promptly.

The result

You can see my collection of lovingly hand-crafted Dockerfiles in my dockerfiles repository.

There are a number of advantages to handwriting all the images I use. The obvious one is that they’re all built how I want: there are no extraneous dependencies, they’re all based on the same small set of base images (rather than pulling around 10 different versions of debian), nothing tries to also run a DBMS in its container, etc.

This level of customisation goes further, though. Because I’m packaging the software myself, I can tweak how it’s built to fit my needs. A couple of things I run need their own TLS certificates separate from my normal HTTPS setup, so I bake my certwrapper tool in to manage those; I can even set the build flags on certwrapper to only enable the particular DNS provider I personally need (thus avoiding dragging in clients for AWS, GCP, etc). Some software like Hashicorp Vault has an optional web interface that I don’t need, so I simply don’t enable it in the build. These changes save build time, reduce image sizes, in some cases improve runtime performance, and generally reduce the attack surface of what’s running in the container.

It’s also been a great way to learn more about how software is distributed. Writing a Dockerfile is not that distant from writing a PKGBUILD file for an Arch Linux package, or the equivalent for other distributions. In a couple of instances I’ve googled how to solve a particular issue, and found an Arch or Void linux maintainer asking the upstream project about the exact same issue.

Finally, all the images I build I push to my own registry so there are obviously no rate limiting issues. Standing up a service (assuming the Dockerfile has been written!) is amazingly quick because the base layers are all shared and cached, and the registry is a lot physically closer than Docker Hub. Bootstrapping this whole thing becomes an interesting problem because the image for the registry is stored on the registry, but I’ll leave that discussion for another post…

Have thoughts that transcend nodding? Send me a message!

Related posts

Reproducible Builds and Docker Images

Reproducible builds are builds which you are able to reproduce byte-for-byte, given the same source input. Your initial reaction to that statement might be “Aren’t nearly all builds ‘reproducible builds’, then? If I give my compiler a source file it will always give me the same binary, won’t it?” It sounds simple, like it’s something that should just be fu...

Docker reverse proxying, redux

Six years ago, I described my system for configuring a reverse proxy for docker containers. It involved six containers including a key-value store and a webserver. Nothing in that system has persisted to this day. Don’t get me wrong – it worked – but there were a lot of rough edges and areas for improvement. Microservices and their limitations My goal was to follow the UNIX philo...

An introduction to containers

I’m a huge fan of (software) containers. Most people I know fall in to one of two camps: either they also use, and are fans of, containers, or they haven’t yet really figured them out and view them as some kind of voodoo that they don’t really want or need. I’m writing this short guide to explain a little how containers work - and how running something in a container isn&rs...

{% figure "right" "Shelf showing a variety of artisanal containers" %} I run a fair number of services as docker containers. Recently, I've been moving away from pre-built images pulled from Docke...