Docker reverse proxying, redux

Published on

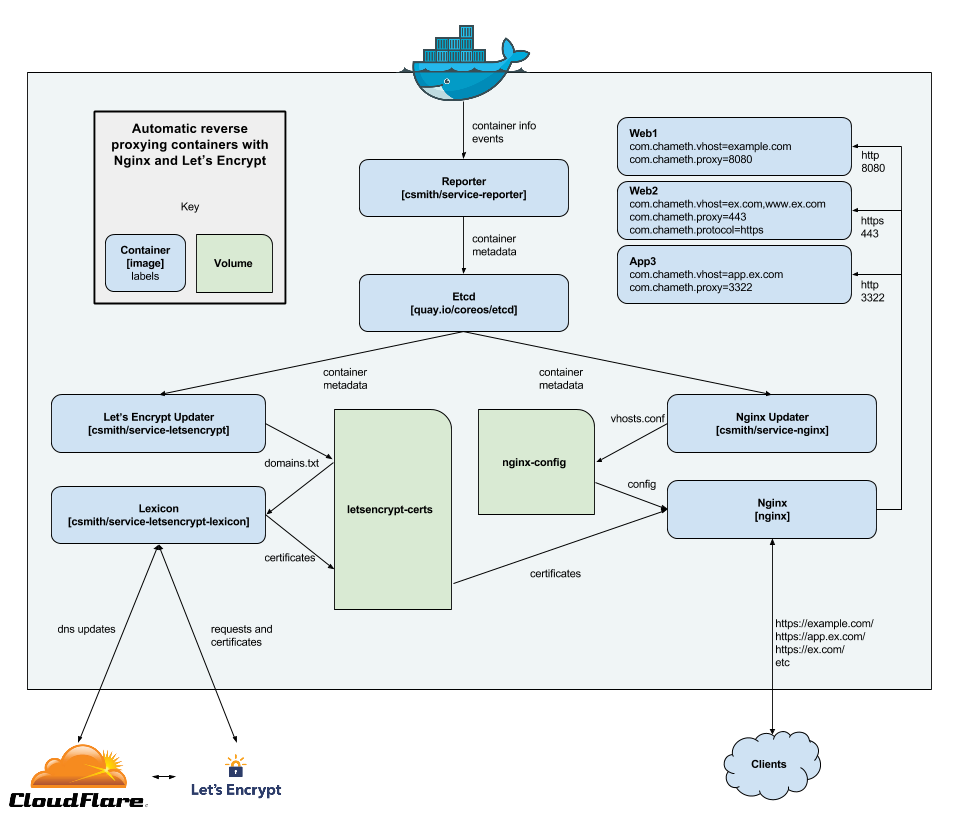

Six years ago, I described my system for configuring a reverse proxy for docker containers. It involved six containers including a key-value store and a webserver. Nothing in that system has persisted to this day. Don’t get me wrong – it worked – but there were a lot of rough edges and areas for improvement.

Microservices and their limitations

My goal was to follow the UNIX philosophy of “do one thing and do it well”. Unfortunately, that doesn’t really work when applied to network services that have to interact with one and other. UNIX tools are built upon a common file system and simple data passed over STDIN. Microservices don’t have that shared foundation. You could make one: companies that use microservices in anger often have a team that deals with the “developer experience” of creating and using microservices. But as a solo developer that’s not something I wanted to spend my time doing.

This became very apparent when trying to debug issues. In the UNIX world, if your series of commands piped together does something strange you can simply echo the data at various stages. Not so much when that data is flying around on a network, going into and out of things like etcd. Trying to figure out why a certificate hadn’t been acquired was a case of searching through logs from four containers, none of which had particularly good logging. There are many ways to get insight into what’s happening with microservices but, again, that’s not something I wanted to do myself.

Over time, and with experience in other projects, I came to realise that microservices only really make sense if you’re unable to deploy a monolith. For tech companies this naturally happens when different teams contribute to the same service: splitting it out into smaller services that are wholly owned by individual teams makes sense. For solo developers, that never happens. You can still gain the other benefits of microservices – such as code separation and having clearly defined APIs – by sticking to certain coding standards.

Proxy inconveniences

As well as being unhappy with the microservice nature of the solution, I wasn’t pleased with nginx. If you requested an unknown domain, nginx would use the first server block in its config to serve a response, instead of sending an “unrecognised name” alert as I wanted. It was a minor issue, but it irked me.

So from nginx I switched to haproxy. It has a strict-sni option when configuring

TLS connections which makes it behave properly. It also performs a lot better for

this type of workload than nginx. All was well for a while, but then I started getting alerts

that requests were occasionally failing. I couldn’t reproduce the issue, but

my nightly jobs to build and push containers managed to hit it nearly every

night, causing them to fail.

After some investigation, I found that the haproxy developers had refactored the header parsing code, and neglected to properly reset flags when multiple requests were sent over the same connection. There was a patch, but it wasn’t released. No problem, I thought, I’ll just cherry-pick it onto the last release… Except that haproxy use Git in the most convoluted manner I’ve ever seen – they have one repository per release. This makes it harder to patch, but it also made me question whether I trusted them to ship stable software: there were no tests for the header parsing code (which is both fundamental and finicky, the perfect target for tests), the source code management was weird, and they didn’t seem in any rush to patch this bug.

Not long after that issue, Greg managed to encounter another bug where haproxy returned a 500 error whenever the upstream server replied with a particular, perfectly valid, header. The die was cast – it was time to move to something else.

Not Invented Here syndrome

Looking for a new solution, there were many more options than back in 2016. I’m still convinced, however, that anything exposed to the Internet should not have access to run docker containers. It’s the modern equivalent of running a CGI script as root. That single requirement eliminates most off-the-shelf solutions. What do you do when nothing quite meets your specific requirements? You make something yourself! My new solution has two components: Dotege and Centauri.

Dotege is a replacement for the microservices that monitored containers and obtained certificates. It’s fundamentally a templating engine - whenever the containers change, it evaluates a template and saves the result to disk. The template has access to details about the containers, their labels, ports, and so on. Dotege can also obtain certificates from Let’s Encrypt, and raise a signal against another process whenever the template or certificates change. I used this to generate the configuration and certificates used by haproxy for a while, and more recently changed the template so that it works for Centauri.

Centauri is my own reverse proxy. It’s configured using a simple text file and can also obtain certificates from an ACME provider. It doesn’t serve static content, has no knowledge about docker, and avoids the other bells and whistles that adorn most reverse proxies. It also has good test coverage to ensure that I don’t, say, accidentally break header parsing.

As a software engineer I enjoy writing software, but I also enjoy running simple, easy to understand software. That’s what I’ve achieved here: it’s very easy to identify where the problem is if anything goes wrong, both are small Go programs rather than vast sprawling C monstrosities, and their interaction is primarily through a file written to disk that can be inspected or edited as needed.

Have thoughts that transcend nodding? Send me a message!

Related posts

Automatic reverse proxying with Docker and nginx

Over the past few weeks I’ve gradually been migrating services from running in LXC containers to Docker containers. It takes a while to get into the right mindset for Docker - thinking of containers as basically immutable - especially when you’re coming from a background of running things without containers, or in “full” VM-like containers. Once you’ve got your head a...

An interesting Tailscale + Docker gotcha

As I’ve written about before, I use Tailscale for a lot of things. I thought I had it set up in a reasonably secure manner, but I recently noticed a problem. I use Tailscale’s ACLs to limit what each node can access, based on the tags I apply to it. So an app node can’t access anything via Tailscale, while an integration or server node can access things tagged with either app or ...

Finding an awkward bug with Claude Code

I recently encountered a bug in one of my projects that I couldn’t immediately figure out. It was an issue in Centauri, my reverse proxy. After its config was updated, I noticed it stopped serving responses. Looking at the logs, I could see it was obtaining new certificates from Let’s Encrypt for a couple of domains, but I’d designed it so that wouldn’t block requests (or s...

Six years ago, [I described](https://chameth.com/docker-automatic-nginx-proxy/) my system for configuring a reverse proxy for docker containers. It involved six containers including a key-value store ...