Shoring up SSHd configuration

Published on

I recently came across a useful tool on GitHub called ssh-audit. It’s a small Python script that connects to an SSH server, gathers a bunch of information, and then highlights any problems it has detected. The problems it reports range from potentially weak algorithms right up to know remote code execution vulnerabilities.

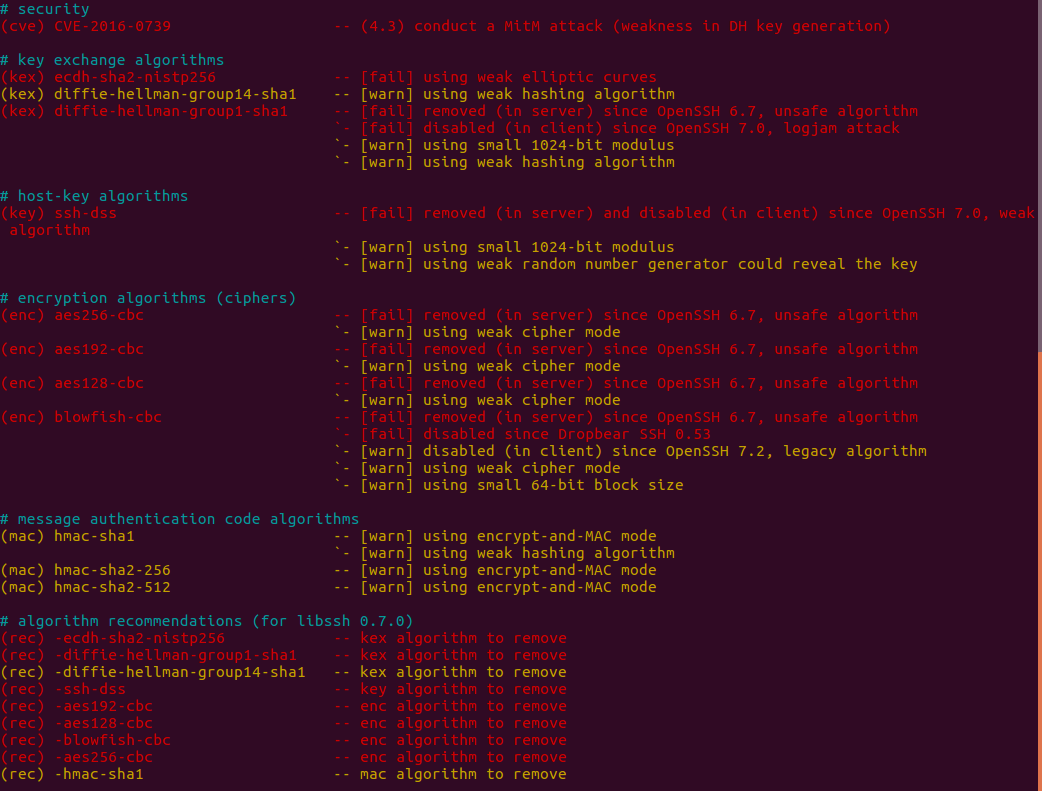

This is the kind of output you get when running ssh-audit. In this particular example, I’m looking at GitHub’s SSH server and have filtered the output to just warnings and failures:

Output of ssh-audit pointing at GitHub’s SSH servers

GitHub’s a bit of a special case, as they’re trying to cope with scores of developers pushing code: they can’t disable weaker algorithms without also stopping lots of people being able to use their service. Still, from the output you can see that ssh-audit has spotted a known vulnerability (CVE-2016-076) and has a lot to say about the various types of supported algorithms.

Background: crypto algorithms used by SSH

Establishing an SSH connection is a moderately complex endeavour, and various parts involve the use of a number of different cryptographic algorithms:

The first such algorithm is the key exchange algorithm. This is the process by which the client and the server agree on a shared key that will be used later. Next comes the host-key algorithm; this is how the server proves its identity to the client. Most SSH users will be familiar with warnings like the following:

$ ssh server.example.com

The authenticity of host 'server.example.com (11.22.33.444)' can't be established.

ED25519 key fingerprint is SHA256:rPVMho1fhEkJqvgce/8iAl353dX5QkGT9F3uCFndsa.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)?

The warning means that the SSH client doesn’t recognise the server’s key, and

is asking the user to confirm it. If the key changes later, the SSH client

will refuse to connect. In the warning above you can see the algorithm used

by the server was ED25519.

Next up is the encryption algorithm, which handles actually encrypting the data sent over the connection. Finally comes the message authentication code algorithm, commonly referred to as ‘mac’. The mac algorithm is effectively responsible for signing each message as a proof that it came from the other party.

Following the recommendations

ssh-audit’s recommendations are pretty easy to follow. It points and shouts at a particular algorithm, and you configure SSHd to not allow it. This is a snippet from my new SSHd config, which gets no complaints from ssh-audit:

HostKey /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key

HostKey /etc/ssh/ssh_host_ed25519_key

KexAlgorithms curve25519-sha256@libssh.org

Ciphers chacha20-poly1305@openssh.com,aes256-gcm@openssh.com,aes128-gcm@openssh.com,aes256-ctr,aes192-ctr,aes128-ctr

MACs hmac-sha2-512-etm@openssh.com,hmac-sha2-256-etm@openssh.com,umac-128-etm@openssh.com

What’s more interesting is the reasoning behind some of the algorithms removed.

The ecdh-sha2-nistp series of key exchange algorithms are subject to a

sidechannel attack described in a paper in 2014.

Some people are also concerned about the involvement of NIST, and the

potential for backdoors. Various other key exchange algorithms

use too small a number of bits in the key exchange (e.g.

diffie-hellman-group1-sha1, which uses 1024). Others still use known-bad hash

algorithms (e.g. diffie-hellman-group14-sha1, which uses an acceptable 2048

bit modulus, but relies on SHA1 hashes). ssh-audit only treats the use of SHA1

as a warning, but there’s no compelling reason to keep it around if you’re

using remotely modern clients to connect. Similarly the host-key DSA algorithm

uses a 1024 bit key, so should be disabled.

Many of the rejected encryption algorithms use basically-broken algorithms

(3des-cbc and arcfour for example). Some of the remaining are block ciphers

with small block sizes, which makes them weak (e.g. blockfish-cbc uses a

block size of 64 bits).

Many of these concerns also apply to mac algorithms (e.g. eliminating

hmac-md5, hmac-sha1-etm@openssh.com, etc, as they use weak hash algos).

Of particular note, OpenSSH supports the hmac-ripemd160 and

hmac-ripemd160-etm@openssh.com algorithms. RIPEMD160 isn’t that common but,

like SHA1, is considered to be weak. One other concern with mac algorithms is

the order in which the encryption and mac attachment are performed.

Encrypt-then-mac is the preferred way of doing it (i.e., the message is

encrypted, then a MAC of the ciphertext is attached). The default used in SSH

is encrypt-and-mac, where the mac of the plaintext is attached after

encryption. Attaching the plaintext mac potentially leaks information (a mac

is designed to provide integrity, not confidentiality, after all). The

encrypt-then-mac algorithms are indicated by the -etm suffix.

Other changes

In addition to the ssh-audit inspired changes, I took the time to review the rest of my standard SSH configuration. The config touches on a few areas; I’m only going to highlight a couple of them:

PubkeyAuthentication yes

RhostsRSAAuthentication no

HostbasedAuthentication no

ChallengeResponseAuthentication no

PasswordAuthentication no

Here all authentication methods other than public key are disabled. A decent key (used in combination with good crypto algorithms!) is drastically harder to brute force than a very good password. It’s also less prone to accidentally being copied into the wrong place, provided to the wrong server, etc.

- UsePrivilegeSeparation yes

+ UsePrivilegeSeparation sandbox

Switching UsePrivilegeSeparation from ‘yes’ to ‘sandbox’ tells OpenSSH to

employ kernel sandbox mechanisms on the unprivileged process. This adds another

layer of defence in case there’s a severe exploit in OpenSSH itself.

An unexpected side effect

After reconfiguring OpenSSH, all of my servers stopped reporting SSH brute force attempts. Every day prior to the change saw hundreds of connections and, after rate limiting and automatic banning blocked a fair chunk, about two dozen unsuccessful login attempts. With the new algorithm selections in place, there were still hundreds of connections, but no failed login attempts at all. A closer look at the logs showed this:

fatal: Unable to negotiate with 1.2.3.4 port 55025:

no matching key exchange method found. Their offer:

diffie-hellman-group14-sha1,

diffie-hellman-group-exchange-sha1,

diffie-hellman-group1-sha1

Apparently not a single one of the clients trying to bruteforce their way in supported the one key exchange algorithm I now allow. I guess at some point they’ll be updated with a modern crypto stack, but until then it’s going to be oddly peaceful…

Have thoughts that transcend nodding? Send me a message!

Related posts

Securing all the things with 1Password

For many years I’ve been a keen user of Bitwarden. Recently I’ve had a lot of small paper-cut problems. The browser extension was redesigned and just doesn’t quite work how I expect any more. The prompt to save new login info misfired more than it worked. The mobile app stopped background refreshing properly. No one issue was enough to make me want to leave Bitwarden, but it defi...

Why you should be using HTTPS

One of my favourite hobbyhorses recently has been the use of HTTPS, or lack thereof. HTTPS is the thing that makes the little padlock appear in your browser, and has existed for over 20 years. In the past, that little padlock was the exclusive preserve of banks and other ‘high security’ establishments; over time its use has gradually expanded to most (but not all) websites that handle ...

How I use Tailscale

I’ve been using Tailscale for around four years to connect my disparate devices, servers and apps together. I wanted to talk a bit about how I use it, some cool features you might not know about, and some stumbling blocks I encountered. I’m not sure Tailscale needs an introduction for the likely audience of this blog, but I’ll give one anyway. Tailscale is basically a WireGuard o...

I recently came across a useful tool on GitHub called [ssh-audit](https://github.com/arthepsy/ssh-audit). It's a small Python script that connects to an SSH server, gathers a bunch of information, and...